The Swannanoa Tunnel

An American Railroad Uncovered Story

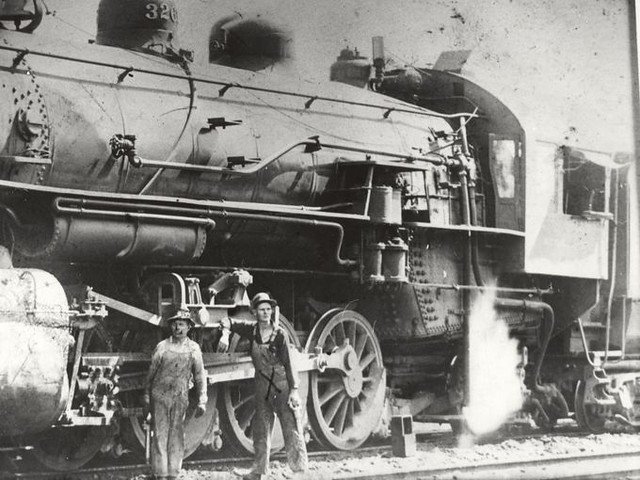

The late 19th century was the era of industrial boom in the United States, in great part due to the construction of cross country railroad lines – like the transcontinental railroad – that allowed for speedier and safer transport of goods, leading to increased prosperity. From the 1860s to the 1900s, large passages of train lines were built, completely changing the American landscape. This story is frequently told and celebrated as a core part of America’s history, with specific focus on railroad tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, James J. Hill and Jay Gould. But the communities who built these railroads are often left out of the dominant narrative: Native Americans, Irish and other European immigrants, African Americans, and Chinese immigrants labored tirelessly to build the railroads that shaped U.S. history. Their stories are often the last to be mentioned in our history books, if they are there at all.

Today, we explore the story of the Swannanoa Tunnel, a railway tunnel in North Carolina that spanned nearly from the state’s Eastern border all the way to the Atlantic seaboard. The Swannanoa Tunnel is an 1,832-foot tunnel that runs through Swannanoa Mountain, and passes close by the city of Asheville. By 1889, within a decade of the tunnel’s completion, Ashevill grew from a rural town of about 2,500 people into a booming city of over 10,000, in large part due to its construction.

A song named after the tunnel also exists, which has historically been discussed within the context of commemorating Asheville’s growth. However, the true meaning and origin of the song has been repeatedly misconstrued through a series of white-washed revisionist accounts. Today, thanks to new research committed to uncovering the original purpose of the song, we know that it was written and sung by the African American laborers who worked on the tunnel’s construction, often men from local prisons who labored at gunpoint.

The Swannanoa Tunnel

The Western North Carolina Railroad (WNCR) was a state-owned corporation tasked with building a portion of the railroad line that connected the country from east to west. According to the Bitter Southerner, the WNCR found that it was most cost-effective to force an uncountable number of wrongfully imprisoned African American men and women to work on the construction crew, laboring in deadly conditions: the weather posed a fatal risk, with many workers dying of pneumonia; the use of nitroglycerine risked cave-ins and devastating accidents; and the guards served as a constant source of fear and violence.

There are several stories that exemplify this fact: there’s a legend that two brothers working on the construction crew walked away, ignoring everyone’s warnings to return. Legend says they were killed by armed, white officers who oversaw the tunnel’s construction. It is widely known that the tunnel’s construction workers were subjected to working at gunpoint. There’s also a well-documented story that recounts the time 19 shackled men drowned when their transport sank into the Tuckasegee River. One of these men, Anderson Drake, saved a guard, but remained a “convict laborer” because the guard accused Drake of stealing his wallet. Drake was whipped on the word of the guard he had saved.

At the time, official accounts portrayed the construction of the tunnel as an emblem of progress – man’s domination of nature. In reality, though, it also represents the hundreds of people who lost their lives building it, many of whom were buried along the Swannanoa Tunnel tracks in mass graves.

The laborers were underfed, poorly housed, and under-clothed. Penitentiary doctors mostly ignored the workers’ illnesses and the labor the workers were tasked with was frighteningly inhumane (The Bitter Southerner). James W. Wilson, the president of WNCR and a former Confederate officer, needed to deliver an engine to Buncombe County, moving it from east to west of the Swannanoa Gap. Simultaneously, Governor Zebulon Vance, also a former Confederate officer, needed Wilson to succeed in order to keep his position as governor. It occurred to these two men that the best way to transport the engine would be to lay down temporary tracks on the east side of the gap and tie together hundreds of men, mule, and oxen, and then force them to haul the 17-ton engine up and over the slope using only ropes and backstraps – These workers were quite literally forced to pull a train engine over a mountain on their backs.

Once the railway was finally completed, Wilson and Vance took all the glory. The reports that came out in the press and those documented in historical records oftentimes completely erased the incarcerated workers from the history of the railroad. Claims spread that the construction had been “at last accomplished by the resolute courage and discriminating judgment of men who were for the most part citizens of the community” (The Bitter Southerner).

The Song

“Swannanoa Tunnel”, sometimes known as “Asheville Junction”, began as a “hammer song”: a genre of work song that is rhythmically driven to help laborers time the strike of their hammers as they’d make holes in rock for nitroglycerin to blow up large sections of the mountain. Though the timing and the poetic pace of the song always stayed the same, the lyrics of the song were often changed and elaborated, sometimes in a completely improvised manner. This tune was not only practical, but it also became a form of creative resistance and many of the lyrics included commentary on their forced labor:

“Asheville Junction

Swannanoa Tunnel

All caved in, babe

All caved in.

When you hear that

Hoot owl squawling,

Somebody died.

Somebody’s dead.”

The history of how this song was appropriated by white culture is exemplary of many stories of American music. Residents from the neighboring towns heard the prisoners’ singing, and the song started catching on. Cecil Sharp, an English folk song collector, visited North Carolina and believed that songs from the region, including “Swannanoa Tunnel”, were actually English “cultural orphans” based on historically English folk songs, seemingly untouched by the Industrial Revolution. In Sharp’s accounts of the song, he changed the lyrics to include his distorted conclusion and titled the song “Swannanoa Town, O.”

Later on, a man by the name of Bascom Lamar Lunsford documented the song as “an old labor song.” However, there was sparse mention of the African American people that created the song or the concept of “convict labor” in his accounts and versions of the song. Lunsford recorded the song for the first time in 1935, and through his commentary of the song turned it into a Southern, white, working-class anthem.

Then in 1955, Arthur Moser, another white Western North Carolina folklore academic, recorded the song for his own album North Carolina Ballads. Moser does, in fact, credit Black forced laborers as the source of the song, but he ends up using Sharp’s incorrect lyrics. In the album notes, Moser claimed that “the people in the area, proud of the song and the things it helped to accomplish, adapted it to their own devices when it no longer served as a work song,” (The Bitter Southerner), in order to account for the use of Sharp’s lyrics. Subsequent recordings of the song led to its growing popularity, making its way to the West Coast. As the song spread, its origin became more obscure, and it was predominantly performed by white artists. Even recently, in 2014, three-time Grammy winner Bryan Sutton included it in his album Into My Own.

Nevertheless, recent research and historical findings have uncovered the song’s true backstory and, in the process, also uncovered a little more information on the true, multi-faceted history of the United States. As Silkroad continues to develop its new project, American Railroad, we’ve been inspired to learn more about the music and the communities that helped shape this country. Dedicated to illuminating the impact the African American, Chinese, Indigenous, Irish, and other communities had on the creation of the U.S. railway lines, this project means to uncover untold stories such as the one surrounding “Swannanoa Tunnel.”

To learn more about the American Railroad initiative and all of its undertakings, use this link.

Sources:

Bigger, Ken. “Swannanoa Tunnel.” Sing Out!, Sing Out!, 23 July 2012, https://singout.org/swannanoa-tunnel/.

Kehrberg, Kevin, and Jeffrey A. Keith. “Somebody Died, Babe: A Musical Cover-Up of Racism, Violence, and Greed.” The Bitter Southerner, 4 Aug. 2020, https://bittersoutherner.com/2020/somebody-died-babe-a-musical-coverup-of-racism-violence-and-greed.

Neufeld, Rob. “Visiting Our Past: Convict Labor Built the Railroads Here.” The Asheville Citizen Times, The Citizen-Times, 3 Mar. 2019, https://www.citizen-times.com/story/life/2019/03/03/visiting-our-past-convict-labor-built-railroads-here/2992778002/.

“Railroads in the Late 19th Century.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/railroads-in-late-19th-century/.

Weidman, Rich. “Swannanoa Gap Tunnel.” NCpedia, 2006, https://www.ncpedia.org/swannanoa-gap-tunnel.